Renovating the PAB Black Box

So we couldn’t take on our renovations without considering the Black Box.

When we turned the building that was originally a rehearsal hall and workshop and then a makeshift church into what we believed to be the first black box theatre in Nassau, we had no idea that this would be the lifeline of the Dundas when the pandemic hit. We were just fulfilling a dream. We wanted a theatre where we could take risks, where we wouldn’t have to worry about filling 332 seats to cover our costs, where it didn’t cost us $3000 a month just to turn on the lights and the air conditioning, where we could take risks and fail without jeopardizing our existence, and this was going to be it.

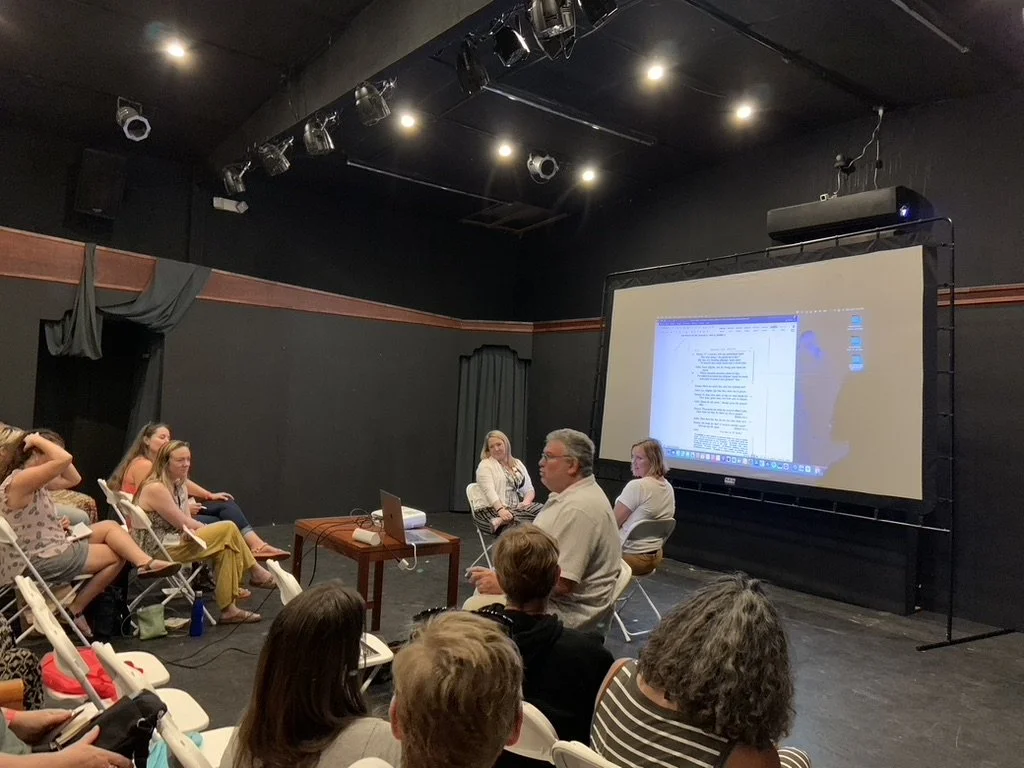

For the first years of its existence, the Black Box operated alongside the main stage theatre as a second venue. It was something that was easy to rent for people who wanted a place to show movies, hold meetings, or put on shows that they were not sure would or could draw huge audiences. It was an intimate space and an experimental space, and it was a great place to stretch our audiences and our actors. It collapsed the distance between performers and audiences. Actors were no longer standing in a proscenium box looking blindly into the glare of lights and performing to an audience they could hear and feel but not see; they were close enough to look into people’s eyes, close enough to touch their audience if they so chose. It was frightening and liberating and it changed the way we did theatre a little bit.

Little did we know that the Black Box would be the theatre that would keep the Dundas alive.

By now many of our patrons and supporters know that when COVID closed down the theatre, our spaces were deeply impacted. Nature, in the form of rodents, birds and insects, took up residence in the buildings; nature in the form of humans who otherwise had no home took up residence on the property in general. When we re-opened, we were able to address the termite issue in the WVS main stage theatre, but the Black Box was a different matter. There were too many trees too close to it, we were told; the tenting would have to wait till we removed them. But we didn’t have the money to remove them, and we needed to pay our bills, so we soldiered on.

Like the WVS Main Stage, the PAB Black Box was a termite haven. Most of its interior was wooden, after all. The theatre, the backstage and the foyer were all separated by a little bit of sheet rock and a lot of pretty thin plywood built onto wooden frames. The frames in the backstage prop area were supported by braces of two by four nailed into the floor, which made them pretty sturdy but which also impeded the use of that space. The frames comprising the black box theatre proper were supported by braces attached to the outer walls.

All of this wood had been food for termites pretty much ever since it had been put in, and during the lockdown, when there was no human traffic in the space to speak of, the termites had been feasting non-stop. We returned to the theatre for classes and rehearsals and readings in 2021, and were greeted by small piles of frass (termite dust) in the foyer, at the bottoms of the walls, and all around the interior of the Black Box. We knew it was bad when the stage crew of one show accidentally hit one of the braces when moving a set piece and it fell on their heads, light as paper and as hollow as an Aero bar.

I suppose our motto is: when faced with a bad situation, be audacious. We had no choice; the Black Box was our only source of income. So we doubled down. Instead of closing the space, we made it as active as possible. From Shakespeare in Paradise 2022, which opened in September, we kept the Black Box alive for the whole of the next year, embarking on the Year of Bahamian Theatre, which presented a play a month for thirteen months, bookended by Shakespeare in Paradise 2022 and 2023. Then we produced the Ringplay Season between March and June 2024, and mounted Shakespeare in Paradise 2024 between September and December. Somehow, around that activity, we were able also to rent out the space every now and then.

But the Black Box needed tender loving care. For one thing, there were leaks which were getting more and more dramatic. When it rained, water would get through the outside in various ways. One of them was a weird sort of alchemy; we would walk into the theatre and have to wade through puddles of water which gathered along the western wall and seeped under the walls to spread across the stage floor. We eventually traced that issue to a leaking gutter which seeped into the wall around the old windows and then came down the walls. Another was a leak which formed in the backstage area, dripping onto and around an ancient filing cabinet which eventually began to rust as a result. The third was the most spectacular. It appeared on the stage itself, somewhere around downstage left, and regular patrons will remember the matter of fact ways in which casts learned to bring in chamber pots and buckets while performing their parts, place them down, or even—once or twice—flip open an umbrella when the scripts called for it.

So our renovations couldn’t take place without including the Black Box. A chunk of that $340,000 from the government was earmarked for roof repair and the removal of all the wood in the place to rebuild with less susceptible materials. And the day Arsenic and Old Lace closed, that work started.